A billboard on I-75 advertising the Appleton Art Museum in Ocala, Florida reads “Connecting Art with Life.” That is what I have always wanted to do for my students, but have often been frustrated because I did not know quite how to do it. However, I truly believe that the new way of thinking about curriculum which has been shown to me this semester will help me make them realize how art throughout history, and the making of new art, is relevant to their lives, whether or not they decide to become artists later on.

Many of the big ideas I have been introduced to as foundations for curriculum building are ideas I have been interested in, and think about as I go about my daily life as well as while making art. However, I had never really thought about making them a main part of my teaching. The concept of organizing lessons around a big idea is exciting, and developing an entire curriculum based on one big idea has been very satisfying. Doing so shows students that the ideas behind all great pieces of art unifies them, which is part of what makes the art itself timeless. It also shows them that the ideas are bigger than merely the art world, but extend to other fields, as well as issues that they individually deal with in their world today.

I have been impressed by how much more complex and interesting a lesson plan is when you base it on student problem solving and student choices rather than a step-by-step process that produces a predictable result. These emphases connect art with life in that they teach students about a part of life that is key: making choices and solving problems. This is something we do every day, no matter what our walk in life. It seems to me an art curriculum that recognizes this, and helps students to think more critically, would be much more effective and relevant in the life of a student than one focused merely on skill-building.

At first, this seemingly more open-ended approach looked as though it would leave little room for skill building. However, I have learned that I do not need to throw skill-building out of the window, but it is actually something I should incorporate while I am teaching the big idea. This also helps connect art with life, because it helps students see that skills they are learning connect directly to the big idea they are exploring as they do their problem solving, since the skills help the students to accomplish the task before them. It enables me to be somewhat rigorous about teaching the skills, too, as long as I give students clear expectations, showing them and teaching them how to do each skill, one at a time. Too often I have expected students to intuitively know how to handle different media, doing things such as blending and shading without including those skills in my lesson. This has caused a gap between my assessment and my instruction. That is one area in which I need to improve. I also need to make sure I slow down and show them what I expect. Just because I know what I’m looking for does not mean that they do.

The new ways of teaching art that I have learned about this semester have added a new dimension to the way I think about teaching art, and I know they will have a huge impact on my teaching. A good teacher is one who explores his field alongside his students. I feel that the mindset that has been presented to me as I have taken this course will move me toward becoming a better teacher in this way, and this excites me.

Thursday, June 19, 2008

Tuesday, June 17, 2008

Moving Toward Conceptual Curriculum Planning

When I started putting together my first curriculum, I thought that a helpful bit of information to consider would be my recollection of the art projects I did when I was in school. However, to my dismay, I could not remember many of the art lessons I had as a student. Most of my art education experience in the Florida Public School system is pretty much a blur.

I resorted to talking to friends of mine who were seasoned teachers. They gave me books and pages of old lesson plans which ended up becoming a starting point for my curriculum planning. The two themes I saw in all of these lessons were a chronological presentation of art history, and the elements and principles of design. These two ideas have formed the framework of my curricula ever since I have started teaching art. One thing I liked most about these frameworks is that they made it very easy for me to decide what to do next. After a lesson on Lascaux cave paintings, it was obvious that Ancient Roman art would be a good place to go. By the same token, a project focusing on shape naturally follows a lesson on line.

This seemed to work fine for a couple of years, especially since the elements and principles were new concepts to me (I hadn’t covered them in my music degree), and art history was so exciting in itself. I really thought it was quite an accomplishment to get them to interact with historical art, even if they were producing their own piece in the style of a Van Gogh, or copying a Monet. And if I could get them to think about the way art can be broken down into elements, and how to critique art according to principles, I thought I would be satisfied. But there were many times when I wished that my students’ artmaking experience could be more like mine is—an organic process of creation. I found so much more satisfaction in teaching independent projects some of my students would do when participating in county-wide and nation-wide contests than I did teaching my normal classes, because I could talk with each of them and help them to come up with ideas that were relevant to their interests, and that inspired them to create.

Why was it that I eventually enjoyed teaching my curriculula so much less than these individual projects? In retrospect, I think my frustration with my curricula lied in its exclusion of the first part of the creative process: generating ideas. Many of the projects in my lessons were primarily mimetic. Maybe I was either assuming I could not teach it, or I was assuming that my students could not do it. Maybe I was considering the technical aspects of the art-making process to be more important to teach than the creative thinking aspects. The consequence is that many of my students have difficulties coming up with ideas when I leave projects more open-ended. This is something that I intend to fix as I write my new curriculum. It is true that the technical side of art is much more straightforward, and it is difficult to make good art with little technical skill. However, without the ability to come up with an idea, what good is technical skill to an artist? Therefore, my key concept for my students to explore will be “Where do artists get their ideas?”

I resorted to talking to friends of mine who were seasoned teachers. They gave me books and pages of old lesson plans which ended up becoming a starting point for my curriculum planning. The two themes I saw in all of these lessons were a chronological presentation of art history, and the elements and principles of design. These two ideas have formed the framework of my curricula ever since I have started teaching art. One thing I liked most about these frameworks is that they made it very easy for me to decide what to do next. After a lesson on Lascaux cave paintings, it was obvious that Ancient Roman art would be a good place to go. By the same token, a project focusing on shape naturally follows a lesson on line.

This seemed to work fine for a couple of years, especially since the elements and principles were new concepts to me (I hadn’t covered them in my music degree), and art history was so exciting in itself. I really thought it was quite an accomplishment to get them to interact with historical art, even if they were producing their own piece in the style of a Van Gogh, or copying a Monet. And if I could get them to think about the way art can be broken down into elements, and how to critique art according to principles, I thought I would be satisfied. But there were many times when I wished that my students’ artmaking experience could be more like mine is—an organic process of creation. I found so much more satisfaction in teaching independent projects some of my students would do when participating in county-wide and nation-wide contests than I did teaching my normal classes, because I could talk with each of them and help them to come up with ideas that were relevant to their interests, and that inspired them to create.

Why was it that I eventually enjoyed teaching my curriculula so much less than these individual projects? In retrospect, I think my frustration with my curricula lied in its exclusion of the first part of the creative process: generating ideas. Many of the projects in my lessons were primarily mimetic. Maybe I was either assuming I could not teach it, or I was assuming that my students could not do it. Maybe I was considering the technical aspects of the art-making process to be more important to teach than the creative thinking aspects. The consequence is that many of my students have difficulties coming up with ideas when I leave projects more open-ended. This is something that I intend to fix as I write my new curriculum. It is true that the technical side of art is much more straightforward, and it is difficult to make good art with little technical skill. However, without the ability to come up with an idea, what good is technical skill to an artist? Therefore, my key concept for my students to explore will be “Where do artists get their ideas?”

Thursday, May 29, 2008

Reflecting on "The Conversation Game"

Since it is the end of the year, I will not at this point be able to use "The Conversation Game" in the way I would like to. It appears to be very useful in helping students generate ideas, and showing them that ideas for art can come from all of life. Ideally, we would play this game at least four times throughout the semester, and students would also use their sketchbook and journal entries to build up a collection of ideas from which they can draw (no pun intended).

My seventh graders played the game this morning. They enjoyed it very much, and I wasn't surprised. Of course, I don't know of many middle school students that wouldn't enjoy a game centered on talking with other students. Instead of verbally sharing the questions with each other at the end, they wrote them on the board. Here are some of the questions they wrote:

"If you could change your name, what would it be?"

"Where is your favorite campsite?"

"What is your favorite sport, and why?"

"What are you going to do over the summer?"

"If you could live in any time period, what would it be?"

Although I had an overall positive response from my students, and they came up with creative questions and answers which could easily contribute toward artistic inspiration in the future, I am not sure how well this works as a game. Our game this morning ended in a tie, since no two groups came up with the same question. At this point, I would like to try to add an element to this game.

My seventh graders played the game this morning. They enjoyed it very much, and I wasn't surprised. Of course, I don't know of many middle school students that wouldn't enjoy a game centered on talking with other students. Instead of verbally sharing the questions with each other at the end, they wrote them on the board. Here are some of the questions they wrote:

"If you could change your name, what would it be?"

"Where is your favorite campsite?"

"What is your favorite sport, and why?"

"What are you going to do over the summer?"

"If you could live in any time period, what would it be?"

Although I had an overall positive response from my students, and they came up with creative questions and answers which could easily contribute toward artistic inspiration in the future, I am not sure how well this works as a game. Our game this morning ended in a tie, since no two groups came up with the same question. At this point, I would like to try to add an element to this game.

Some Thoughts on "The Conversation Game"

While writing a new art curriculum, in search of a way for my students to explore where artists get their ideas, I came upon “The Conversation Game,” which was developed by Marvin Bartel, Ed. D. Follow this link to see the lesson: http://www.goshen.edu/art/ed/self.html In the article accompanying the lesson, he wrote about one of his biggest challenges as a teacher:

“I had a problem. I was good at teaching skills, but teaching technicians was not enough. My teaching needed to find ways to communicate this autobiographical nature of art to students in a way that made their own mind, soul, experience, and values available to them and more important to them. Just assigning this was not enough to see it happen. I know there are those who say art cannot be taught, but that did not keep me from trying.”

I have been wondering how I could inspire my students and teach them to get excited about coming up with their own ideas. It sounded to me like this teacher was on the same wavelength. One focus that I have found to be particularly helpful in area is getting students to ask questions. I have mostly explored different ways of getting students to ask questions about artwork. However, the goal of the Conversation Game is to get students to ask questions about each other.

“When students practice the ability to form questions, they are exercising their critical thinking abilities and skills. Learning to ask good questions is learning critical and artistic thinking habits.” Until reading this article, I have been thinking of art as a catalyst for asking questions, not the other way around. Although I have heard artists refer to their artwork as being explorations of ideas and concepts, I hadn’t thought about the fact that this was necessarily advantageous to the artist.

Dr. Bartel stresses the fact that artistic ideas come from all of life, and they come when you least expect it. Part of coming up with great ideas is learning to take a real interest in life, and a great place to start is taking interest in the lives of others. Central to this game is asking questions about other students’ lives, and points are awarded for coming up with the most original questions. I think this approach to teaching creative thinking would be successful, since students might not be as prone to getting bogged down by a supposed need to come up with some grand idea out of thin air. It shows them in a very practical way how one idea can lead to another, and how great ideas start from talking, thinking about, and living everyday life. I also like the fact that it helps the students think outside of their own world, and become interested in someone else’s. This is something that I think we especially need to strive to teach at the middle school level. I am going to use this lesson today with my 6th and 7th grade classes, and am excited to see how it works out. In the future, I intend to use this toward the beginning of the school year.

“I had a problem. I was good at teaching skills, but teaching technicians was not enough. My teaching needed to find ways to communicate this autobiographical nature of art to students in a way that made their own mind, soul, experience, and values available to them and more important to them. Just assigning this was not enough to see it happen. I know there are those who say art cannot be taught, but that did not keep me from trying.”

I have been wondering how I could inspire my students and teach them to get excited about coming up with their own ideas. It sounded to me like this teacher was on the same wavelength. One focus that I have found to be particularly helpful in area is getting students to ask questions. I have mostly explored different ways of getting students to ask questions about artwork. However, the goal of the Conversation Game is to get students to ask questions about each other.

“When students practice the ability to form questions, they are exercising their critical thinking abilities and skills. Learning to ask good questions is learning critical and artistic thinking habits.” Until reading this article, I have been thinking of art as a catalyst for asking questions, not the other way around. Although I have heard artists refer to their artwork as being explorations of ideas and concepts, I hadn’t thought about the fact that this was necessarily advantageous to the artist.

Dr. Bartel stresses the fact that artistic ideas come from all of life, and they come when you least expect it. Part of coming up with great ideas is learning to take a real interest in life, and a great place to start is taking interest in the lives of others. Central to this game is asking questions about other students’ lives, and points are awarded for coming up with the most original questions. I think this approach to teaching creative thinking would be successful, since students might not be as prone to getting bogged down by a supposed need to come up with some grand idea out of thin air. It shows them in a very practical way how one idea can lead to another, and how great ideas start from talking, thinking about, and living everyday life. I also like the fact that it helps the students think outside of their own world, and become interested in someone else’s. This is something that I think we especially need to strive to teach at the middle school level. I am going to use this lesson today with my 6th and 7th grade classes, and am excited to see how it works out. In the future, I intend to use this toward the beginning of the school year.

Monday, April 28, 2008

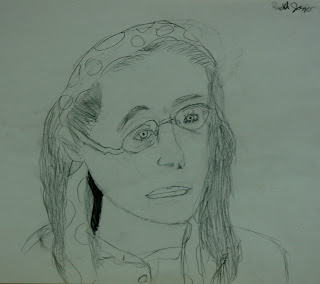

Regular Contour Drawings

These are some regular contour drawings my students did a couple of weeks ago. Although some of them really enjoyed blind contour drawing, most students let out a sigh of relief when I told them they didn't have to draw with a shield over their hand. I think the blind contour drawing helped them to draw more of what they actually saw, rather than what they thought they saw--even when they were allowed to look at their paper (I did stress, however, that they should be looking at their subject 90% of the time).

Friday, April 25, 2008

Letter to An Artist

Yesterday, each of my students picked an art print from our classroom print collection and wrote a letter to the artist of the painting reproduced.

Here are a few of their letters:

Dear Johannes Vermeer,

I love your painting! The colors brown and red sit very well together. Is that supposed to be you painting in the picture?

I think the way you put such a detailed picture in the background is an awesome idea! Was this back when Spain still hadn’t found America? I think that your painting of another painting was a brilliant idea!

Sincerely,

Jasmine

Dear Mr. Hopper,

I love your work (November, Washington Square). It is a very realistic looking picture. I like how it shows real American life at that time.

This picture is of a city so you should do one of the country out west. I also like how the sky is painted with the blue in the middle. I think you are great at painting cities.

Sincerely,

Carrie

Dear Mr. Monet,

Why did you choose all those bluish colors? Were you sad about someone dying at sea? I like the colors you chose for this particular painting.

Were you angry when you painted this? All of your strokes look like they were done in anger, or in a rush. Get back to me on that, okay?

Sincerely,

Rachel

Here are a few of their letters:

Dear Johannes Vermeer,

I love your painting! The colors brown and red sit very well together. Is that supposed to be you painting in the picture?

I think the way you put such a detailed picture in the background is an awesome idea! Was this back when Spain still hadn’t found America? I think that your painting of another painting was a brilliant idea!

Sincerely,

Jasmine

Dear Mr. Hopper,

I love your work (November, Washington Square). It is a very realistic looking picture. I like how it shows real American life at that time.

This picture is of a city so you should do one of the country out west. I also like how the sky is painted with the blue in the middle. I think you are great at painting cities.

Sincerely,

Carrie

Dear Mr. Monet,

Why did you choose all those bluish colors? Were you sad about someone dying at sea? I like the colors you chose for this particular painting.

Were you angry when you painted this? All of your strokes look like they were done in anger, or in a rush. Get back to me on that, okay?

Sincerely,

Rachel

Monday, April 21, 2008

Reflections on Teaching Creative Thinking

As I have read further on creative thinking, two characteristics of creative thinkers that have particularly struck me as interesting are: “a desire to work hard and at the edge of one’s abilities and knowledge” and “a belief in doing something well for the sake of personal pride and integrity.” Both of these characteristics are taken from a list developed by Dr. Craig Roland, referring to studies done by T.M. Amabile and D.N. Perkins in the 1980s. I wonder if these two attributes are necessary in order for a student to have the patience to show other traits on this list, such as:

• a willingness to drop unproductive ideas and temporarily set aside stubborn problems

• a willingness to persist in the face of complexity, difficulty or uncertainty

• a willingness to take risks and expose oneself to failure or criticism

• a desire to do something because it’s interesting or personally challenging to pursue

• an ability to concentrate effort and attention for long periods of time

I have always considered the drive to work hard and learn new skills and information, simply for the pleasure of doing so, to be something that people are born with—some to a greater extent than others. As I have worked in the arts, it has also been very apparent to me that doing something well is very satisfying, whether or not anyone else notices.

How, as an art educator, can I help my students to develop these attitudes? It sometimes feels like when I'm trying to do so I am swimming upstream in a culture that seems to teach kids to need instant gratification, a numerical score for so much of their work, and incentives for doing day-to-day tasks. External motivation is all over the place, and as a result, students seem to expect us to reward them every time they stretch themselves in some way. I also think our schedule-oriented society teaches kids that ‘faster is better.’ There are so many times that I feel like my students are racing against the clock to get their work done, and I struggle with getting them to slow down and really take their time on what they are doing.

One suggestion I have read—and tried—is to give students activities that they find intrinsically motivating. Activities that give students many opportunities to make their own decisions are encouraged. This gives the students more of a sense of ownership about their work.

However, there are some students in my classes who do naturally take their time on every single project, careful to produce pleasing results. For these students, it does not matter what the assignment is, or how many decisions they were allowed to make. These students encourage me, but they also challenge me. Why is it that some students exhibit this tendency so much more consistently than others, regardless of the assignment? Shouldn’t I be able to help all of my students develop such an intrinsic desire to work for a long time in order to achieve high quality work?

At this point, one thing I can focus on is breaking projects down into a series of defined steps. Lately, I have required my students to brainstorm ideas on paper before even starting to draw, using tools such as a web chart. This year I have very often required my students to make sketches before working on a final piece--something that I did not do in my earlier years of teaching. I am also realizing the importance of verbally emphasizing how carefully and slowly I like to work while giving demonstrations in class, hoping students will model this when they engage in their activities.

These are small steps toward what seems to me to be very important goals. They are external, and I can only hope that they will affect my students internally. It is my view that developing desires for quality and intellectual growth within students is key to promoting creative thinking.

• a willingness to drop unproductive ideas and temporarily set aside stubborn problems

• a willingness to persist in the face of complexity, difficulty or uncertainty

• a willingness to take risks and expose oneself to failure or criticism

• a desire to do something because it’s interesting or personally challenging to pursue

• an ability to concentrate effort and attention for long periods of time

I have always considered the drive to work hard and learn new skills and information, simply for the pleasure of doing so, to be something that people are born with—some to a greater extent than others. As I have worked in the arts, it has also been very apparent to me that doing something well is very satisfying, whether or not anyone else notices.

How, as an art educator, can I help my students to develop these attitudes? It sometimes feels like when I'm trying to do so I am swimming upstream in a culture that seems to teach kids to need instant gratification, a numerical score for so much of their work, and incentives for doing day-to-day tasks. External motivation is all over the place, and as a result, students seem to expect us to reward them every time they stretch themselves in some way. I also think our schedule-oriented society teaches kids that ‘faster is better.’ There are so many times that I feel like my students are racing against the clock to get their work done, and I struggle with getting them to slow down and really take their time on what they are doing.

One suggestion I have read—and tried—is to give students activities that they find intrinsically motivating. Activities that give students many opportunities to make their own decisions are encouraged. This gives the students more of a sense of ownership about their work.

However, there are some students in my classes who do naturally take their time on every single project, careful to produce pleasing results. For these students, it does not matter what the assignment is, or how many decisions they were allowed to make. These students encourage me, but they also challenge me. Why is it that some students exhibit this tendency so much more consistently than others, regardless of the assignment? Shouldn’t I be able to help all of my students develop such an intrinsic desire to work for a long time in order to achieve high quality work?

At this point, one thing I can focus on is breaking projects down into a series of defined steps. Lately, I have required my students to brainstorm ideas on paper before even starting to draw, using tools such as a web chart. This year I have very often required my students to make sketches before working on a final piece--something that I did not do in my earlier years of teaching. I am also realizing the importance of verbally emphasizing how carefully and slowly I like to work while giving demonstrations in class, hoping students will model this when they engage in their activities.

These are small steps toward what seems to me to be very important goals. They are external, and I can only hope that they will affect my students internally. It is my view that developing desires for quality and intellectual growth within students is key to promoting creative thinking.

Thursday, April 17, 2008

Turning Curriculum Around

The idea of the ‘Backward’ Curriculum Design Process is a new one to me, even though I’ve been in the field of teaching for several years. An article I read recently on the subject pointed out that many teachers focus on what they are teaching more than what the students are actually taking away with them. They are concerned first with things like materials and what activities the students will do rather than the learning goals. Unfortunately, this reminds me of the way I am used to planning my curriculum.

To me, music and art (at first glance) seem to revolve around activities. In teaching these, my main goal has often been merely to engage my students and help them to improve on a particular skill. This article describes much of what has gone on in traditional design to be ‘hands-on’ rather than ‘minds-on.’ I think a fair amount of my teaching has encouraged my students to actively apply their minds to what they are doing, in order to produce desired results. ‘Big ideas,’ those universal truths which are relevant across the ages, in multiple disciplines, were pleasant highlights that my students and I would happen upon along the journey. However, for most of my teaching career, I don’t think they have necessarily been the focus of my teaching.

Studies have shown that children are prone to look for reason and intentionality behind most things. I especially have noticed this attribute while teaching adolescents. Students’ questioning about the reason behind activity is a good thing, and since much of my teaching has been activity based, I have not often enough used it to my advantage. I have thought it difficult to deal with while teaching students a skill I consider to be intrinsically valuable (especially when they do not at first agree with me). However, it should be something I actively embrace and encourage. Building connections among universal truths and all of the skills I wish to teach in art is a large challenge, but one well worth pursuing. I am realizing more and more that I need to use the universal truths as scaffolding rather than ornamentation.

I am wondering if a large hurdle for me will be picking a new starting point. For example, I deem skills necessary for good representational drawing to be important. I would like to be assured that my students are taught the basic principles of this and other disciplines that fall into the category of visual arts. Focusing on the practical aspects of my discipline seems to be more challenging when I am starting with universal truths. However, his is a challenge I am definitely willing to take on, as I see that it is the universal truths that hold a curriculum together, connect it with other disciplines, and ultimately show the students that it is relevant to life.

To me, music and art (at first glance) seem to revolve around activities. In teaching these, my main goal has often been merely to engage my students and help them to improve on a particular skill. This article describes much of what has gone on in traditional design to be ‘hands-on’ rather than ‘minds-on.’ I think a fair amount of my teaching has encouraged my students to actively apply their minds to what they are doing, in order to produce desired results. ‘Big ideas,’ those universal truths which are relevant across the ages, in multiple disciplines, were pleasant highlights that my students and I would happen upon along the journey. However, for most of my teaching career, I don’t think they have necessarily been the focus of my teaching.

Studies have shown that children are prone to look for reason and intentionality behind most things. I especially have noticed this attribute while teaching adolescents. Students’ questioning about the reason behind activity is a good thing, and since much of my teaching has been activity based, I have not often enough used it to my advantage. I have thought it difficult to deal with while teaching students a skill I consider to be intrinsically valuable (especially when they do not at first agree with me). However, it should be something I actively embrace and encourage. Building connections among universal truths and all of the skills I wish to teach in art is a large challenge, but one well worth pursuing. I am realizing more and more that I need to use the universal truths as scaffolding rather than ornamentation.

I am wondering if a large hurdle for me will be picking a new starting point. For example, I deem skills necessary for good representational drawing to be important. I would like to be assured that my students are taught the basic principles of this and other disciplines that fall into the category of visual arts. Focusing on the practical aspects of my discipline seems to be more challenging when I am starting with universal truths. However, his is a challenge I am definitely willing to take on, as I see that it is the universal truths that hold a curriculum together, connect it with other disciplines, and ultimately show the students that it is relevant to life.

Thursday, March 27, 2008

Blind Contour Drawing in the Classroom

My students did blind contour drawing for the first time last week. I learned about this drawing method after I started teaching, while reading ‘Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain’ by Betty Edwards. However, I had been taught to draw using a method that was based upon similar principles but was carried out in a different way.

I understood how blind contour drawing would help my students to focus more on what they were seeing and would help them to ‘turn off’ the verbal mode our brains often naturally gravitate toward when drawing. However, I did not understand how doing this activity would help them draw better in the long run. I was not sure how well my students would be able to control their line quality while doing this exercise. I also could not imagine my students really enjoying this exercise or focusing for very long while doing this.

I did some blind contour self portraits and actually enjoyed seeing the results. I realized that it is possible to capture contours very accurately while doing this, and I actually ended up with some interesting and expressive lines.

When we did this in my classroom, I was pleasantly surprised at my students’ reactions to the assignment. Some thought it was fun, and this exercise was so different from the way that we have drawn before in class, that it really caught their attention. I explained what a contour drawing was, and demonstrated by drawing a student’s portrait. I told that during this drawing exercise they would not pick up their pencils, and how this actually can help you gauge the distance between features (I think so, anyway). I emphasized the importance of slowing down and carefully observing all of the slightest nuances of a single line. I demonstrated this, and the students were surprised at how slowly I was expecting them to draw.

I then chose one student from each table to be a model, and explained what ‘outside contours’ and ‘inside contours were, pointing out that it was important to include both in their drawings, but they could decide where in the drawing they wanted to go from one to the other. The students then drew their models ‘in the air.’ Almost all of them drew the outside contours first, and then the inside contours, according to the models. In the second ‘air drawing’ I challenged them to pick a more unusual point to go from outside to inside contour.

We moved on to the actual blind contour drawings, using pencils. I had never thought of using a piece of paper as a shield, to keep the students from looking at their paper. This is something I had used in piano before, but never in drawing. The idea of putting the pencil through the ‘shield’ works very well, and was definitely a new concept to all of my students.

They did one minute, two minute, and five minute drawings. I was delighted to see many of my students fully engaged, trying their hardest to do careful renditions of the portrait models at their tables. Some students were drawing more slowly than they usually do, and my classroom was actually very quiet for almost the entire activity (which isn’t always the case). Many of the drawings they ended up with were descriptive in different ways than their usual drawings were, and were more accurate, in some ways, than drawings where they were allowed to look at their paper.

I think I would like to use this activity in my classes on a regular basis, and I see that as being a possibility since it can be done in short intervals. Our next project will be contour self portrait drawing, and although they will not have ‘shields’ over their hands, I will encourage them to apply the new concepts they learned from blind contour drawings to their self portraits. We will practice some ‘air drawing,’ and my hope is that they will take their time and pay close attention to the contour lines they draw to make their portraits.

Tuesday, March 4, 2008

Ideas Which Stand the Test of Time

Both students and teachers have asked my why it is important for us to study art. A colleague of mine commented the other day that art is fine for those who particularly enjoy drawing, but it isn’t really for everybody, and he has never understood why it is important for us to study art history. People with his point of view are one of my motivations for teaching art.

A prevailing opinion in our society seems to be that art education is superfluous, which is why it is one of the first programs to be ousted when budget cuts are made. Art is not tested in state and national tests, and I haven’t yet heard of a ‘Monet Effect’ (although statistics have shown that children involved in any of the arts tend to have higher grades and test scores). Some would ask, with such a limited amount of time and resources for to teaching our students, is it really advantageous to devote much of that to art education, especially to those who aren’t ‘gifted’ in art, or naturally interested?

I would definitely say that the enrichment provided to students by art education is vital. After all, our ability and need to work creatively is one attribute that makes us distinctly human. Since the beginning of time, people have used their creativity to make sense of their existence and world around them by describing it, reflecting on it, and asking questions about it. In our exploration, we have produced stories, poetry, plays, games, paintings, mathematical equations and scientific theories, resulting in everything from the Enuma Elish to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. It is important for us to keep asking genuine questions about life and our world, as well as listening and responding to those who have already given us their point of view. This is a significant part of our humanity.

The theme of exploration ties all of human activity together, which is one reason art has strong connections to every other field. We aren’t usually quick to group science and math with art. However, once you realize the common motivation for all disciplines, you start to see that each one is a voice in the same great conversation that has been going on for centuries.

How do we, as art educators, impress this idea upon our students? One of the first principles that has impressed me since I’ve started studying art education this semester is the focus of one main idea throughout a unit or year. A ‘unit’ to me has always been a set of lessons with a common theme, such as ‘The Middle Ages’ or ‘Africa.’ However, I am very attracted to using an ‘enduring idea’ as the foundation for a unit instead. An ‘enduring idea’ crosses over the somewhat artificial boundaries we have drawn around individual disciplines, and is significant throughout time. Basing a curriculum on this shows students (and teachers) that art is relevant to all of life.

Ideas in this category might include ‘the relationships between humans and nature,’ ‘similarities and differences between dreams and reality,’ or ‘the nature of time.' In teaching units based on questions such as these, the teacher should incorporate disciplines other than the visual arts which address the same question. For example, a unit on the relationships between humans and time could include discussing John Cage’s 4’33”, and The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dali. Creating rhythm in music and in printmaking could also be explored simultaneously. Lessons should not merely touch on connections among disciplines or tip their hat to the enduring idea, but should be measured by how deeply they challenge students to think about the enduring idea, and by genuine connections made among multiple disciplines.

Putting together a unit based on enduring ideas will take more thought than the units I have been used to, but it is true that you reap what you sew. Such an approach will most likely produce better thinkers, who are more aware of how understanding and creating art is important to every aspect of life.

Wednesday, February 27, 2008

Discussing da Vinci's Drawings

Yesterday we looked at drawings by Leonardo Da Vinci, in preparation for making Renaissance-style drawings from nature. My original goal in this discussion was to highlight his hatching technique, line quality and subject matter. However, as I was preparing for this, I realized it would be a perfect opportunity to touch on a couple of the ‘big ideas’ I had been thinking about emphasizing in my teaching.

In class, we discussed the many different purposes art can have—even within the work of one artist. As we studied drawings of inventions, skeletons, plants, people and animals, we talked about the variety of reasons Da Vinci had for making his work. He drew an object as a way of studying it more carefully, or committing it to memory. He also drew to invent or design something new, or to improve his skill level of drawing a particular subject. Other times he drew in order to make a beautiful drawing as a work of art, or to prepare for the creation of a painting.

This brought us to talk about the fact that sometimes when artists draw, their purpose is not to produce a finished work of art. Instead, the process is more important to them than the finished product. Among other purposes, Da Vinci used the act of drawing to more carefully observe his subject. I am hoping that my students’ experience of drawing from nature will serve the same purpose for them.

Friday, February 22, 2008

The Color Wheel: Variations on a Theme

I walked my students through making a color wheel last week, reviewing the mixing of colors. We also talked about the signicance of complimentary and analogous color schemes. Students then made their own color wheels, having their choice of any medium or form. They came up with some pretty creative color wheels! I encouraged them to 'think outside of the box,' and one student took me quite literally.

Thursday, February 21, 2008

Teaching Students to Think About Art

I have been reading and reflecting on encouraging creative thinking in the classroom. This may be more challenging than it has been in the past. As a society, our abilities to work and think creatively are affected by the ‘instant gratification’ mindset that dominates so many aspects of our lives, from microwavable dinners to e-mail. We have gotten to the point where we take for granted what we hear and see coming from television or the internet. Images are not as thought-provoking as they used to be, since we are inundated by commercial ones on a daily basis. We barely see them after a while. As art educators, we need to train our students to work against this tide—to see art as a process, rather than merely a product—a process wherein they slow down and think about what they want to accomplish, and take time to decide upon the best way to go about doing that.

However, as I’ve read about characteristics that would ideally exist in a ‘mindful’ classroom, I’ll have to admit that my classroom does not exhibit many of these, at least consistently. I think one problem is I dedicate all of my students’ class time to working on art projects, and do not give them time to really think about what they are doing. I discuss their creations with them individually, but have not blocked out substantial time in the class period to focus on talking, as a group, about their work. We also do not spend large amounts of time simply having dialogue about art.

Why do I do this? After all, my classroom routine certainly did not arise out of my artistic habits. When I set out to make a painting, the steps of coming up with an idea, and developing the perfect composition, are very large and important parts of the battle. Throughout much of my teaching career, I have thought that a good way to keep my students engaged was to keep things moving. I have expected my students to be most interested in hands-on activities, so they have dominated my students' class time. However, as an art educator, I should be teaching my students, as a class, to stop and think rather than merely do. The 'thinking' part should be a more important part in my curriculum, one that deserves its own allotted time.

How can I change this? I am attracted to the structure of hands-on activities, so the best way to promote ‘brainstorming’ or ‘information gathering’ time would be in a very structured format. It should be part of the classroom routine, like that of passing out supplies, or cleaning up at the end of the class period.

I have decided to incorporate ‘thinking time’ into my classes by adding a couple of structured activities to the routine. These will consist of regular writing in art journals, and group critiques. Art journals are something I have used sporadically in the past. One reason I did not use them this year was that I did not have a unified vision for the purpose of the journal entries, so I preferred to devote more of the class time to working on projects. However, I am inspired by the idea of focusing on one two larger questions or ideas throughout the year, which would also be reflected in my lessons. The journal assignments would center on these, whether they involved looking at another’s art, reflecting on one’s own art, or coming up with new ideas. I would also like to use the journals as springboards into class discussions. With these discussions, as in the journal assignments, I would focus on asking broad, open- ended questions, and will encourage my students to take time to think about their answers.

The concept of taking class time to do a critique is something that was new to me in my college studio art classes. I found critiques to be motivating and inspiring. They helped me realize that people looked at my paintings and actually thought about why I made them the way I did. This encouraged me to think more about how I chose to express the ideas and emotions I wanted to convey (or at least let me know that my choices did convey ideas and emotions). They also helped me to assess my decisions and feel more confident in developing my artistic voice.

In addition to everything critiques helped me learn about my own art, they also taught me how to engage with another artist about their art. It was here that I learned how to ask the ‘why’ questions about a piece of art. I was also able to see firsthand how a fellow student went about the artistic process, and compare it to my own method.

Until now, I had not thought about using critiques in my middle school classes. However, I would like to try to do this regularly. The day after a project is due, my goal is for my class to be in the routine of spending most of the 50-minute period in a group critique, although every student’s work may not be featured in one day. I may also try breaking my class up into groups of four or five to accomplish this, in order for every student to be critiqued. A good way to start this activity might be to give students a list of questions they might ask the artist, in order to help them develop the ability to ask meaningful questions about a work of art. My hopes for this activity would be that it would have the same effect on my students that it had for me—that it would help them to ask questions and make decisions in a more thoughtful manner.

As I use these two ideas in my classes, it is my hope that my students will develop substantially in various areas of creative thinking. I want them to be able to step back and look at their thought processes, elaborate on their ideas, and take ownership of them. I want them to work on the edge of what they know, and to see the intrinsic value in creating something meaningful. Teaching them to slow down and think carefully would be a significant step in that direction, and devoting time in class to this would help them to see its importance. It is my plan to have both of these practices worked into my clasroom routine within the next couple of weeks.

Friday, February 15, 2008

Paper Mache

In Language Arts, seventh graders are reading 'Call of the Wild' by Jack London. In order to integrate this with Art, they have been looking at Northwest Pacific totem poles and are constructing their own totem pole models using paper mache. They started the building process this week. It was messy......but fun!

Wednesday, February 13, 2008

Where Do Artists Get Their Ideas?

“Artists often get their ideas from their surroundings and experiences.”

A good way to introduce this idea would be to start a class discussion with the question “Where do artists get their ideas?” One common misnomer about artists is that all of their ideas simply pop into their heads from out of nowhere. The mystery of ‘inspiration’ makes some people think that it is a gift that is bestowed upon the ‘enlightened’ artist, with little or no effort on their part, and all they have to do is translate their vision onto a canvas for ordinary people to see. (Granted, there are instances where artists create pieces based on dreams, but even these are technically drawn from life experiences.)

To teach this principle, I could show students a series of several artworks, perhaps by famous artists, and explain how each artwork arose out of the everyday experiences of the artist. Some artists, such as Rosa Bonheur and Edgar Degas, purposefully placed themselves in certain environments, or around certain subjects, to make their favorite subjects part of their everyday experience. Others just made art from that which they happened to see throughout the course of an average day.

Following this discussion, the students could research the art themselves. They could even create and perform skits which involved actual people, places and things which made their way into the work of the artist, and showed a bit of the artist’s creative process. Assessing the students’ understanding in this case would involve evaluating how much of the skit actually linked the artist’s work to the artist’s life, rather than simply showing them as co-existing.

Another way to drive this point home would be to use the students’ art journals. In order to do this, it might be beneficial to have the students focus on studying the lives of a small number of artists throughout the year, by means of internet research, reading time, unit projects and or class discussions. As a starter exercise for multiple classes, I could show them a slide of one of the artists’ works and have the students hypothesize about the inspiration of the artist’s ideas, based upon what they know about the artist’s life. In assessing this, I would to see that the students drew upon the knowledge they had about the artist’s life, or that they tried to look at the subject through the artist’s eyes, in order to come up with their answers.

Students could see this truth at work in their own art by keeping a sketchbook. In using this tool, I would instruct them to draw items, people and places from their lives, and encourage them to incorporate their drawings in class projects. I would especially challenge them to think outside of the box, looking for beauty or interest in objects or places that they might not normally think to create art about. They would be required to write a sentence or short paragraph about their drawings, explaining why they chose to draw what they did, and how each person, place or thing is significant or interesting to them.

In assessing these, I would look to see that the drawings and writings had strong connections to one another, and were, in fact, part of the students’ life experiences. I think this would be easily reflected in the writing and in the detail and uniqueness of the drawings. By doing this exercise they might see firsthand how many ideas an artist tries out in his sketchbook before incorporating one or two of them into his artwork. They would also understand from personal experience how an object that may seem mundane in everyday life can be transformed as the subject of an inspired work of art.

Monday, February 11, 2008

Purposeful Art

I will now explore ways to assess how well my students understand each of these three 'big ideas,' one at a time.

“Art, although it has had a variety of purposes throughout history and different cultures, should have purpose, and should be meaningful.”

In order to stress this to my students, I would teach them about some of the many of purposes art has served around the world, throughout history. I would spend time showing and explaining artworks to them which were used for each of these purposes. We would also spend time talking about art as a language; for example, how artists use color to express mood. Over the course of the year, I would show them multiple works of art. I would spend at least half of the year asking them questions which make them think about what the artist intended their work to do for the viewer, and why they created the work the way they did. I would probably have the students write their answers in an art journal.

I would look for journal entries that show they understand the connections among function, artists’ intentions, and the language of art. The inclusion of each of these considerations in their writing, in a coherent way, would probably show that the students understand how they are related.

My goal for them would not only be for them to come up with thoughtful answers to my questions, but also for them to learn to ask their own thoughtful questions about art. To assess the students’ abilities to ask thoughtful questions, I would change the routine that involved me asking them questions, and would give them the opportunity to come up with the questions themselves. I might ask a different student each day to write one question on the board concerning the artwork, and everyone would answer the question in their journals. Some days they may simply write, and some days we would discuss the questions as a class. Another idea would be for the students to write their questions in their journals, and then answer them. A class discussion may also follow this activity.

In order for students to see how this truth plays itself out their own artwork, I would give them projects that would allow them to express their ideas using visual language. These projects should make them aware of the of the decisions they make while creating art, and their purposes in making them. I have been reading through Engaging the Adolescent Mind by Ken Veith, and have been impressed by the way he wrote a ‘visual problem’ at the beginning of every lesson. Instead of merely giving his students a series of steps, he gave them a problem for them to solve using visual means. I think this gave the students ample opportunity to express themselves by making art that was meaningful to them. It also made it clear that we, as artists, have a reason behind every part of the art-making process; each piece of art is the result of a number of meaningful decisions. Making students aware of this should help them to place importance upon the choices they make during the creative process, strive to express themselves in a way that can be understood by the viewer, and inspire them to ask questions about the art of others.

I would assess how well the students applied the language of visual art to express their ideas or solve a problem by asking them questions about their art. I would ask them how the choices they made in material, color, line, form, etc. work to solve the visual problem presented to them at the beginning of the project. I would also ask them what ideas inspired them as they created their artwork.

“Art, although it has had a variety of purposes throughout history and different cultures, should have purpose, and should be meaningful.”

In order to stress this to my students, I would teach them about some of the many of purposes art has served around the world, throughout history. I would spend time showing and explaining artworks to them which were used for each of these purposes. We would also spend time talking about art as a language; for example, how artists use color to express mood. Over the course of the year, I would show them multiple works of art. I would spend at least half of the year asking them questions which make them think about what the artist intended their work to do for the viewer, and why they created the work the way they did. I would probably have the students write their answers in an art journal.

I would look for journal entries that show they understand the connections among function, artists’ intentions, and the language of art. The inclusion of each of these considerations in their writing, in a coherent way, would probably show that the students understand how they are related.

My goal for them would not only be for them to come up with thoughtful answers to my questions, but also for them to learn to ask their own thoughtful questions about art. To assess the students’ abilities to ask thoughtful questions, I would change the routine that involved me asking them questions, and would give them the opportunity to come up with the questions themselves. I might ask a different student each day to write one question on the board concerning the artwork, and everyone would answer the question in their journals. Some days they may simply write, and some days we would discuss the questions as a class. Another idea would be for the students to write their questions in their journals, and then answer them. A class discussion may also follow this activity.

In order for students to see how this truth plays itself out their own artwork, I would give them projects that would allow them to express their ideas using visual language. These projects should make them aware of the of the decisions they make while creating art, and their purposes in making them. I have been reading through Engaging the Adolescent Mind by Ken Veith, and have been impressed by the way he wrote a ‘visual problem’ at the beginning of every lesson. Instead of merely giving his students a series of steps, he gave them a problem for them to solve using visual means. I think this gave the students ample opportunity to express themselves by making art that was meaningful to them. It also made it clear that we, as artists, have a reason behind every part of the art-making process; each piece of art is the result of a number of meaningful decisions. Making students aware of this should help them to place importance upon the choices they make during the creative process, strive to express themselves in a way that can be understood by the viewer, and inspire them to ask questions about the art of others.

I would assess how well the students applied the language of visual art to express their ideas or solve a problem by asking them questions about their art. I would ask them how the choices they made in material, color, line, form, etc. work to solve the visual problem presented to them at the beginning of the project. I would also ask them what ideas inspired them as they created their artwork.

Friday, February 8, 2008

The Value of Tone

Thursday, February 7, 2008

Three Big Ideas in Art

“If you could teach your students three things, what would they be?”

When I was asked this question last week, I knew it would be very challenging to narrow down what I felt was important in art to three things. From my perspective, there is so much to know about this field, and it is my job to teach as much of it as I can. To try to come up with an answer, I immediately started to tick through the list of elements and principles of design I’ve focused on in my teaching, and tried to decide which ones were most important. I soon realized that picking three of those and deeming them essential would have been as ludicrous as picking three major scales and telling a piano student that knowledge of these was the heart of understanding music. I changed my approach, and started to think bigger than just the ‘how to’ aspect of art.

When I was asked this question last week, I knew it would be very challenging to narrow down what I felt was important in art to three things. From my perspective, there is so much to know about this field, and it is my job to teach as much of it as I can. To try to come up with an answer, I immediately started to tick through the list of elements and principles of design I’ve focused on in my teaching, and tried to decide which ones were most important. I soon realized that picking three of those and deeming them essential would have been as ludicrous as picking three major scales and telling a piano student that knowledge of these was the heart of understanding music. I changed my approach, and started to think bigger than just the ‘how to’ aspect of art.

Yesterday, I came across an interesting quote by George Sand: “Art for art’s sake is an empty phrase. Art for the sake of the true, art for the sake of the good and beautiful, that is the faith I am searching for.” This quote inspired the first principle on my list: Art, although it has had a variety of purposes throughout history and different cultures, should have purpose, and should be meaningful.

I would like to encourage my students to see art in an authentic, meaningful way. Art should help people wrestle with essential questions, or understand some facet of the human experience. This may involve religion, social concerns, or appreciating the beauty of nature. Whatever the artist’s purpose in creating his or her art, ordinary people should be able to connect with it, on some level. Understanding this would encourage my students to try to learn about society and the world through art, and also to strive to make art that is meaningful.

A second truth I would like my students to remember is that artists often get their ideas from their surroundings and experiences. I want them to look for inspiration from people, places and things in their everyday lives. I would also like them to think about the relationships between the works of art they see, and the lives of the artists who created them.

Third, it would be important for my students to understand that sometimes the art making process is more important than the product. Even though art should communicate something to the viewer (and good art naturally will), creating the art is often first and foremost the means by which the artist interacts with his or her environment or experience. Sometimes that is the sole reason an artist creates. It can help the artist understand his or her surroundings more fully. The act of creating can also be the consummation of the artist’s emotional experience toward his or her surroundings.

Even though I have attempted answer to this question here, I know I will ponder it for years, and my answer will probably change multiple times. I do not really think it is possible to pick three principles that are absolutely the most important to understanding art. However, thinking about this question is challenging me to focus on a few essential aspects of art, and emphasizing them in my teaching, rather than trying to teach everything.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)